Giraldus Cambrensis (1146-1223) didn’t know about DNA, so he wouldn’t have used the same terms as ‘the Donald’ to assert his claim to superiority, but there’s little doubt the Medieval self-publicising scholar also believed that he came of a race of winners and took similar delight, not only in identifying, but in creating losers.

Matt Frei’s insightful documentary, ‘Meet the Trumps’ http://www.channel4.com/programmes/meet-the-trumps-from-immigrant-to-president/videos/all/trailer/5279201844001 goes a long way to explain the bizarre phenomenon that is now POTUS (how apposite the acronym for a position of such potency; how reassuring when it referred to Obama).

Frei reveals how Friedrich Trump bequeathed to his son and grandson a conviction that winners are violent and rapacious. They take and take again, because taking is what winners do. Losers are the chumps who aren’t strong enough to hold on to what they have. Friedrich made his fortune supplying alcohol and prostitutes to those losers who thought they needed to dig for gold with an axe.

His son, also unhampered by moral scruples, took advantage of a government house-building scheme to line his own pockets at the taxpayer’s expense. Undaunted by public opprobrium, he passed the baton of self-assurance to the present Trump. Facts, morality, decency: just the impedimenta that keep losers living in Loserville.

The Gerald’s grandfather, Walter, was an immigrant of another kind. He came to England with Guillaume the Norman, who was to conquer a bunch of Saxons with relative ease in 1066. Those tooled-up Normans, with their Viking feistiness, were the winners of that new millennium. Walter’s son was active in dispossessing Welsh losers, and the grandson, cosying up to Henry II, set about creating another set of losers, in Ireland.

Not by the sword, though. His brother, Philip, was representing the family in that endeavour. Just as the Donald’s purchasing of women has not, perhaps, been quite as crude as that of Friedrich, so the Gerald asserted his winner status in a different way from Walter and Philip. He wanted to wield the power of the Roman Church, an authority to which Henry II was subordinate. While Prince John uselessly riled the Gaelic nobles, the Gerald was preparing his books, The Topography of Ireland and The Conquest of Ireland.

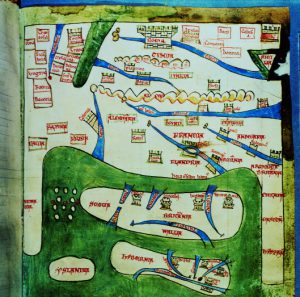

This image (National Library of Ireland), was created for Gerald of Wales’s books on Ireland and is evidence of his outlook. Note the position of Rome at the top of Europe.

And here’s a major difference between our two heroes. The Gerald could wield a dazzling quill. His accounts, which flatter the king, announce that the Irish people are in need of a bit of Norman discipline, the land rich and ripe for exploitation, and the Irish Christian Church practically pagan in its laxity. And they do so with lyrical, embellished prose, and compelling flights of invention. The message: the author is useful, learned and in fact just the sort of man Henry needs to run the Church in England.

And here’s a major similarity. Like the Donald, the Gerald employs logic which operates within a closed loop, so it’s seductive to those who like their thinking ready-to-wear. Encouraging Henry’s Irish ambitions, he suggests the English king is ‘our western Alexander’ (124) and that unlucky island, already occupied by many of our hero’s relatives, should play Henry’s West to Alexander’s East:

Just as the countries of the East are remarkable and distinguished of certain prodigies peculiar and native to themselves, so the boundaries of the West also are made remarkable by their own wonders of nature. For sometimes tired, as it were, of the true and the serious, she draws aside and goes away, and in these remote parts indulges herself in these secret and distant freaks (31).

So a polemic in the guise of an historical account gains currency, and here’s another reminder of the Trump method. The Gerald arranges to publicly read his manuscript over three days in Oxford. He guarantees himself an audience by offering lavish entertainment, and, as F. X. Martin doesn’t quite tell us, tweets about it afterwards: ‘It was a magnificent and costly achievement, […] nor has the present age seen nor does any past age bear record of the like’ (287).

Ah, self-promotion. Martin retails some wonderful samples of the Gerald’s vanity. For example, as a student in Paris, ‘I was then as renowned for beauty of face […] as for elegance of figure’ (282). Another record of Gerald’s unearthed by Martin tells us that ‘the pleasure of listening to his voice drew such a gathering of almost all the teachers together with their scholars, that scarce even the largest hall could contain his audience […] they hung upon his lips as he spoke […] and could never hear enough of his eloquence’ (284).

And just as many Americans have taken the Donald at his own valuation, so it seems did Giraldus Cambrensis, despite the improbability of his Munster island where no one dies, his Connacht island where corpses do not putrefy, his Leinster well which prevents men turning grey, his Wicklow half-man-half-ox, and his accounts of habitual bestiality and cannibalism, achieve a popularity which ensured that his more temperate libel, that of laziness, would endure for at least 900 years. Let’s hope none of the Donald’s slander lasts that long.

Works Cited

Gerald of Wales. The History and Topography of Ireland. Trans. John J. O’Meara. London: Penguin, 1982. Print.

Martin, F. X. ‘Gerald of Wales, Norman Reporter on Ireland’. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 58.231 (1969): 279-92. Print.

Featured image showing an Irish king bathing in a stew of mare’s milk from the Topographia Hibernica.

Really interesting and creative. Inferences I would never have drawn myself.

LikeLike